Picture above: India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi dressing up China's President Xi Jinping and Russia's President Vladimir Putin in Indian style.

By Susmit Kumar, PhD

In 2009, I attended a conference on Indian economy at a US top five business school in a mid-west university. During the first session, I raised the question that, yes, the Indian economy was booming, but its trade deficit had been increasing like the US trade deficit; but whereas the US could pay it by printing its currency India would face a crisis down the line. I also mentioned that I had just published a book in 2008 that had a detailed discussion about the Indian and the global economy. They did not give any direct answer. Rather, after my question they changed the format of questions from the audience (after the first session). In the first session, you'd just needed to raise your hand in order to ask a question but now questions were to be wubmitted on a piece of paper to the moderator and it would be up to the moderator to choose from the submitted questions. They introduced this change because any talk about debilitating effects of the growing trade deficit on Indian economy would have had ruined the conference which core idea was to present the bright side of economic growth in India.

In fact, just two years after the conference, the Indian economy was in the midst of a grave crisis. Due to record trade deficits during 2011-13, the exchange rate of the rupee (vis-à-vis the US dollar) tumbled from 44.17 in April 2011 to 62.92 in September 2013. After the sharp devaluation of the Indian rupee and double digit inflation during 2011-13 due to the high crude oil price, some economists even started to write the obituary of the Indian economy (read: "None of the experts saw India's debt bubble coming. Sound familiar?", The Guardian, UK, August 26, 2013; ‘Fragile Five’ Is the Latest Club of Emerging Nations in Turmoil, New York Times, January 28, 2014).

In the US, university students are taught virtues of so-called US capitalism, painting rosy pictures only of the US economy, and not at all discussing the actual dire economic scenario in the US. Business schools in US universities produce economists and MBAs for the Wall Street and not for the main street, means not for a government that would work for the common people.

There is a revolving door between the Wall Street and the financial organs such as the Treasury Department of the US administration. In nearly all US administrations, Wall Street bankers have held the top positions in the financial organs of the government. Following the end of the term they again rejoin the Wall Street and hence, their allegiance is with Wall Street and not with the common people of the US.

One major criticism of the $700 billion bailout at the onset of 2008 Great Recession by the Bush administration was that all big Wall Street financial institutions were paid in full – Societe Generale received $16.5 billion in payments, Goldman Sachs $14 billion, Deutsche Bank $8.5 billion, and Merrill Lynch received $6.2 billion, and another 12 institutions received a total of $16.9 billion for the full value for their credit-default swaps with American International Group (AIG) which was certain to go bankrupt without the bailout. On the other hand, had the AIG been allowed to go bankrupt, the Wall Street bankers would not have had received even a single cent (“Watchdog: Fed Used Flawed Strategy in AIG Bailout”, abcnews.go.com, November, 16, 2009).

Whenever a country, due to a a FOREX crisis, goes to the IMF, the IMF, mainly manned by the US Treasury Department, forces the country to pay the loaners’ full amount. After watching IMF at work during the 1997 East Asia Economic Crisis, Joseph E. Stiglitz, the 2001 winner of the Nobel Prize in economics and chief economist at the World Bank from 1996 to 1999, wrote in April 2000:

“I was chief economist at the World Bank from 1996 until last November, during the gravest global economic crisis in a half-century. I saw how the IMF, in tandem with the US Treasury Department, responded. And I was appalled” (Joseph Stiglitz, “The Insider: What I Learned at the World Economic Crisis,” New Republic, April 17, 2000).

“The IMF may not have become the bill collector of the G-7, but it clearly worked hard (though not always successfully) to make sure that the G-7 lenders got repaid” (Joseph E. Stiglitz, Globalization and Its Discontents, New York, W.W. Norton, 2003, p 208).

Stiglitz described the crisis very well:

“The IMF first told countries in Asia to open up their markets to hot short-term capital [It is worth noting that European countries avoided full convertibility until the 1970s.]. The countries did it and money flooded in, but just as suddenly flowed out. The IMF then said interest rates should be raised and there should be a fiscal contraction, and a deep recession was induced. As asset prices plummeted, the IMF urged affected countries to sell their assets even at bargain basement prices. It said the companies needed solid foreign management (conveniently ignoring that these companies had a most enviable record of growth over the preceding decades, hard to reconcile with bad management), and that this would happen only if the companies were sold to foreigners—not just managed by them. The sales were handled by the same foreign financial institutions that had pulled out their capital, precipitating the crisis. These banks then got large commissions from their work selling the troubled companies or splitting them up, just as they had got large commissions when they had originally guided the money into the countries in the first place. As the events unfolded, cynicism grew even greater: some of these American and other financial companies didn’t do much restructuring; they just held the assets until the economy recovered, making profits from buying at fire sale prices and selling at more normal prices” (Joseph E. Stiglitz, Globalization and Its Discontents, New York, W.W. Norton, 2003, pp 129-30).

The US economists/MBAs are experts in increasing share prices by squeezing as much money from a firm (keeping it lean and thin, i.e. having as few employees as possible) as possible for the shareholders. They are however not good for a nation’s economy. A country is not a firm. For the development of a country, you need to keep entire population in mind rather than a few shareholders as in case of a firm.

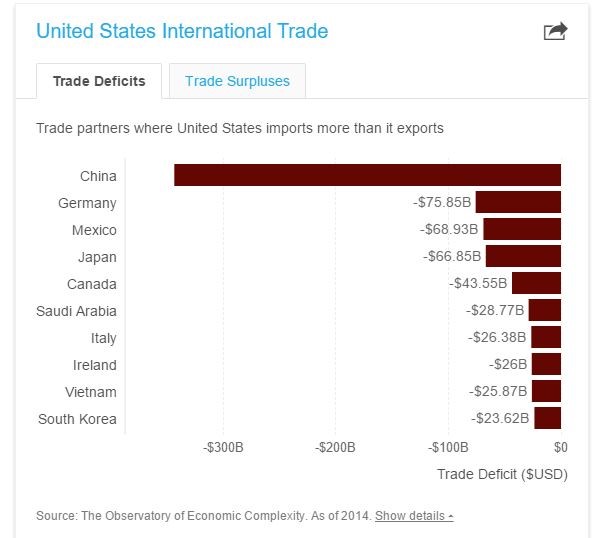

Since the liberalization in 1991, Indian economy is going in the wrong direction as a consequence of being exceedingly dependent on US economists. India has now wasted nearly three decades by following US economic policies whereas the US is actually a bankrupt economy, surviving only by printing its currency, which happenes to be the global currency, in order to fund its twin deficits: its budget and its trade deficits. This has been going on since the mid-1970s (please see my articles: The US Dollar – A Ponzi Scheme; Two Competing Models in the Global Economy; Is "Make In India" Theme Helping Indian Economy? – Part II). India’s trade deficit is the third highest, after the US and the UK, in the world (please see Chart 1). In the case of the UK, due to Margaret Thatcher, the British Prime Minister during 1979-90, the country has been following the “Reaganomics,” i.e. small government, lower taxes, free trade and privatization.

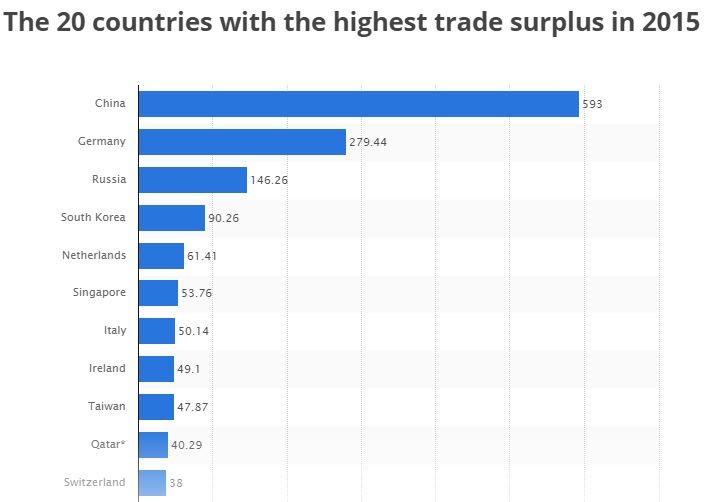

Rather than sending bureaucrats to Harvard University and other prime US academic institutions for management training, the Indian government needs to send them to countries like Germany because the German manufacturing sector still contributes about 25 percent of its GDP as compared to only 11 percent in the case of the United States. For this very reason Germany is still the world’s second-largest exporter (please see Charts 2 and 3) and has not faced the same severe crisis that countries such as the United States and other Western nations have been facing due to emergence of the global Chinese workshop.

"Since the liberalization in 1991, Indian economy is going into wrong direction because of being exceedingly dependent on US economists. India wasted last nearly three decades by following the US economic policy which is actually a bankrupt economy, printing its currency, which happened to be the global currency, to fund its twin deficits – budget and trade deficits since mid-1970s (please see my articles: The US Dollar – A Ponzi Scheme; Two Competing Models in the Global Economy; Is "Make In India" Theme Helping Indian Economy? – Part II). India’s trade deficit is the third highest, after the US and the UK, in the world (please see Chart 1). It is worth noting that due to Margaret Thatcher, the British Prime Minister during 1979-90, the UK has been following the “Reaganomics,” i.e. small government, lower taxes, free trade and privatization. For this very reason like the US jobless recovery since the 2008 Great Recession (“Why the U.S. Has a Monopoly on Jobless Recoveries,” Noah Smith, Bloomberg News, January 23, 2017), India has been experiencing jobless growth (“Where are the jobs?,” Shweta Punj and MG Arun, India Today website, April 20, 2016). According to a recent report, while the economy is growing at just over 7% per year, jobs increased by just 1.1% last year, covering eight key sectors of the nonfarm economy. An earlier report had pegged joblessness at a five year high of 5% in 2015, and underemployment at a staggering 35% of the over 15-years labor force (“Economy growing at 7%, jobs at 1%”, Subodh Varma, Times News Network, May 19, 2017)."