Prabhakar Overland

Prabhakar Overland

The Copenhagen climate summit (December 2009) was no Xmas gift to the world. In its aftermath Canadian climate advocate George Dvorsky of Sentient Developments listed five reasons1 for the summit’s failure to reach an internationally binding deal on the climate crisis:

- Nation-states are far too self-serving

- Democracies are too ill-equipped and irresolute to deal with pending crises

- Isolationist and avaricious China

- The powerful corporatist megastructure

- Weak consensus on the reason for global warming

One may or may not agree with all of this in detail (for instance about China being most isolationist and avaricious) but Dvorsky seems realistic enough on principle.

1. Nation-states are far too self-serving

Yes, diplomats usually keep more than one eye on their home base. But for how much more will they be able to relay on the specifically national to serve their country’s interests? The Nation – homeland of natives, of those “born” there – is a notion heavily invaded these days. At present the global migrant population stands at 214 million2, qualifying as no. 5 among the world’s most populated countries above Brazil and below Indonesia.

Other factors busy eating away at national dogmas and prejudices are:

- Rapidly evolving global work environments for many who remain working in their home country

- Mass tourism with nearly 1b arrivals3 a year worldwide; of people who “travel to and stay in places outside their usual environment for more than 24 hours and not more than one consecutive year for purposes not related to the exercise of an activity remunerated from within the place visited.”

- Trans-border marriages; in the EU alone there are 16 million international couples4

Simultaneously multinational corporations are doing their bit by continuing to apply commercial pseudo-culture as a most efficient marketing method for its goods and services. Transnational giants such as Coke and McDonald’s may like to pay attention to local cultural sensitivities when mapping out their marketing campaigns. Still their purely globalising effect is lost on no one. And the uniform stamp of the global entertainment industry is even more felt.

And then there is technology, the all time most globalising factor.

A main result and quality of our global melting pot is its growing resonance to the global call in itself. Even rim countries, who may experience less exchange and mixture than more centrally placed countries, are being heavily influenced by the global. The innermost secret is that we all want to know and share in the emerging universal commonwealth of new sensibilities and futurist products. We all want to be there when the great takes place.

In all this may we expect the limited national to be able to hold out much longer to the expansive idea of actual world governance? Quite the opposite, we expect the peoples of the newly awakened one world to realise the need of a global political system as the most natural thing there is.

2. Democracies are ill-equipped and irresolute

Party-based democracies are ill-equipped and irresolute, it is true. Any structure depends wholly on its fundamental base. Party-based democracy depends wholly on political parties. This is clearly seen if we compare the short period leading up to elections, when party machines are drummed up to win over the electorate, to the entire period between elections — which may amount to 95 per cent of the time — when contact between politicians and the electorate is conducted mostly via the media and often in a questionable way. By and large there is very little direct contact between professional politicians and the people.

So why do we continue with this system? The concept of party-based democracy is a contradiction in terms: Democracy is supposed to be by, for and of people, not by, for and of political parties. The present system seems not to further people’s interests but parties’ interests first and foremost. Such a system can therefore only serve to confuse people about their rights and common values.

Do you know the origins of the political party system? Political parties started out hundreds of years ago as interest groups at royal courts. Prominent representatives of powerful circles of landowners, merchants, industrialists, etc. would congregate and parley in front of the monarch about issues close to their heart. Those far from humble beginnings of modern parliamentarism evolved into today’s far from humble modern professional party machines.

In response to why politicians arrived at the Copenhagen summit without even having consulted the people they represent in the matter, Dvorsky offers that this would only work if the ‘people of the world’ were universally educated about the intricacies of the issues (including scientific, economic, cultural and political considerations) and disarmed of their petty selfishness and local biases.

Exactly our point. Democracies can only survive if they transform towards becoming more active at grass-roots. As a matter of fact we hold that democracy may survive as a form of governance only if it is liberated from the twin clutches of party-ship and big business, you know, vote-buying and all that.

In a nutshell, the present party-based “democratic” set-up should move on to becoming people’s economic democracies. In the process the economy would be localised and essential policy-making globalised, which would fit the idea of world government hand in glove.

3. Isolationist and avaricious powers

People all over the world seem to think the Chinese keep to themselves in most ways. The US on the other hand are famous for being outgoing. Do such labels really matter? As far as climate policy is concerned it is the US that most infamously has refused to follow up on Rio 92 and Kyoto. If they had chosen otherwise, a precedence might have been established that even the up-and-coming China would have found impossible to run away from, even in areas of human rights. As things stand, the US has no moral right to question any amount of holding back from others, and labelling others is never a way towards a shared understanding.

Global policies need to be framed by taking into account the interests of all in areas of immediate common concern, such as water, food, peace, etc. World government principles and operative structure needs to be evolved in such a way that policies will actually be materialised without fail. A suggested list of such world government pre-requisites is found here.

4. Powerful interest groups

Like-minded people always seek each others company. Groups and lobbies of a common understanding will keep pushing for their own interests. History bears witness to a series of eras where different collective mentalities — the laborious, the conquering, the intellectual and the acquisitive — ruled one after the other. Not your flavour of the month, more the dominance of centuries. The stronger mentality rises, remains for some time, and then falls as another begins its rise on the tail of the reign of the previous.

At present everything may be measured in commercial figures but it will not remain that way forever, or even for much longer. At a time when we all can observe sure signs of the collapse of global capitalism, the observant will also be able to witness the birth of a new set of values that will guide humanity into what’s coming.

Among other things, the new era seem to be characterised by world society foundation. Even then, special interest groups will continue to make their voice heard. They will attempt to leave their mark on society to the best of their capacities. It is the job of a world government to take all such general and special interests into account and make them work for the benefit of all people.

5. Weak consensus

Dvorsky’s fifth and last point reaches back to the one about isolationist behaviour on part of powers. Only a properly formed world government, with a proportionally seated lower house (population-based representation) and a veto-empowered uniformly seated upper house (for instance two reps per country), can secure that correct information is being tabled and processed. This double lock mechanism is essential while dealing with sensitive cross-border issues such as water, food, pollution control, and a host of other resources issues. Otherwise small nations will be totally marginalised.

Value-oriented Governance

The late Ananda Marga head Acarya Shraddhananda once offered that the most important idea of the 20th Century was ecology.5 His argument was that it made us understand the inter-dependence of all things created. The political reality of our 21st Century world is that we are all inter-dependent and have to act on it.

We are indeed one. Human beings share a common value base different from the motivations of some party structure or the machinations of the political world. In the words of educator Ac. Shambhushivananda,

“Values are those psychic projections which form the basis of human thoughts, attitudes, behaviours and actions. A value is … a kind of unwritten collective agreement or understanding on what is worthwhile and necessary for the well-being of a person, relationship, community and a culture.”

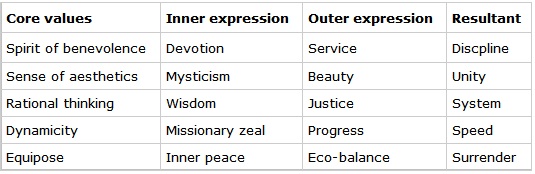

Table of values, from Ac. Shambhushivananda

A universal value base, clearly defined and set forth in a world constitution, would provide a benchmark for what is expected and accepted throughout the world. It would then be the job of the world government to realise those values in the interest of all.

Notes

1 http://ieet.org/index.php/IEET/more/dvorsky20100110/

2 www.migrationinformation.org/datahub/charts/worldstats_1.cfm

3 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tourism

4 www.cbsnews.com/stories/2011/03/16/ap/europe/main20043901.shtml

5 In A Spiritual Treasures of Jewels, Ananda Marga Publications, 1993.

Copyright The author 2011